During his publishing years Traven was a mystery man. No photos existed, no address, no nationality. The world first heard the name B. Traven in 1925. The novels came in rapid succession.

All but the Death Ship are set in Mexico. The Cotton Pickers, published the same year as The Great Gatsby, is about an American "down on his luck" working subsistence jobs in southern Mexico. This is the backdrop for Treasure as well. The Death Ship has the American performing the lowliest duties on the worst of ships. The crew is doomed because their ship is to be sunk for the insurance money. All the books were first published in German during the inter-war period and found a big audience in the freewheeling Weimar republic. When the nazis came to power, Traven's novels, full of contempt for authority, were banned and publication moved to Switzerland. This was nearly everything that was known about Traven. The novels were coming from Mexico with a Mexican setting with American protagonists and published in Germany. Whoever Traven was, he seemed to know a lot about southern Mexico, its people and how to live and survive there.

He claimed to be an American who spoke, wrote and thought in English, and had translated or had them translated into German. Above all he said details of his life are nobody's business, at the same time he said he washed up on shore or was a cabin boy at 10 who traveled the entire world and never went to school. Nobody was really ever sure who he was. Even today, while one theory tracing him back to his birthplace has emerged, there are many other stories and some researchers who believe the many false trails and tall stories he told about himself have misled the experts.

The consensus is that Traven wrote a German political newsletter in the 1910's under the name Ret Marut. After a briefly successful political upheaval, he may have been captured, possibly was going to be executed, and possibly escaped. Some scholars may be more definite, but the only account I have seen was written by Marut himself, and the only thing that is certain is that Marut-Traven was a recreational liar.

Will Wyatt of the BBC believed he tracked Marut to his birthplace in present day Poland. No one else has brought forward a more credible story with as much evidence. Marut according to this version was born Otto Feige. He had a fairly ordinary childhood. It doesn't sound anything like Traven's own autobiographical writing (which might speak in its favor). It doesn't explain his love or knowledge of the sea, his preoccupation with being a bastard, his supposed facility with Americanisms, or his late entry into Mexico and nearly instantly sending novels back to Germany. So modern scholars, whether they just can't let go of the mystery, or their suspicions are valid, are skeptical of the Wyatt solution.

Nevertheless its fairly well accepted that after a brief imprisonment in England for being an undocumented alien, Marut, on the run from Germany, landed in Southern Mexico in 1924, and changed his name. Berick Traven Torsvan, and variations thereof, worked and lived in Tampico, visited Chiapas. He studied for a time at University in Mexico City, subjects like Mexican history, literature and archeology, which would serve him as a novelist. He made 3 known expeditions to Chiapas, at least one with a guide who was familiar with the lumber camps, which would form the basis for his series of novels referred to as the Mahogany novels. Traven wrote in detail of the debt slavery and brutal conditions native Mexican Indians endured, conditions which were largely gone by the time he arrived.

Traven's politics in Germany was largely an individualistic approach, though he took part in the socialist Bavarian Soviet Republic, for a few weeks, and had to leave the country for it. His newsletter was mainly a one-person operation. He is usually referred to as an anarchist, someone who doesn't accept any authority. Once in Mexico he quickly became convinced that Indian society was more noble, sustainable, and preferable to capitalism or communism, fascism or socialism. He didn't like church authority any better than government. He had nearly lost his life in Germany in a political battle, and appeared to distrust authority in general.

By 1940, he has written all the major novels he will write. Germany was at war in 1939. There were many German nationals in Mexico. They were in Mexico because they had been expelled or fled, or were nazi spies. Mexico required them to register. Traven, maintaining he is American, born in San Francisco, did not surface. However Traven's books were well known to the German people in Mexico and they made attempts to find him. Some journalists even wrote they believed him to be Ret Marut. They considered Traven a kindred sort, a pioneer, an old friend who had preceeded them and was successful in Mexico. When Traven's German publishing house was taken over by Nazis in 1933, he emphatically withdrew publishing rights.

According to the official story, most of which came from Traven's self-promoting newsletter many years later, Esperanza Lopez Mateos read a Traven book - pirate Spanish versions of Rebellion and Bridge both existed - and wrote in Aug 1939 asking about film rights for "Rebellion" and "Bridge." Turned down, she translated "Bridge in the Jungle" from English to Spanish (first English publication was 1938) on her own time. Traven was so impressed that he gave her the job, met with her, and they were so taken by each other that she instantly became his business manager.

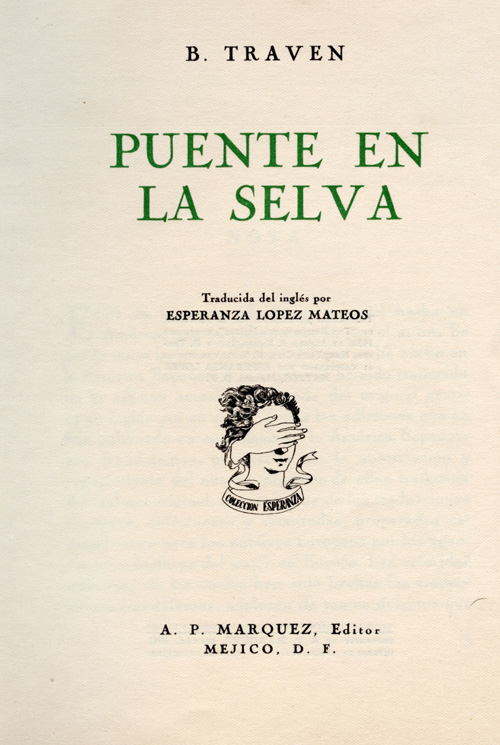

In April 1941 appeared Esperanza's first translation, "The Bridge in the Jungle (Puente en la Selva)." In addition to translation credit, she has a logo on the title page. In the introduction, Traven says that all previous Spanish editions of his work are fraudulent, poorly taken from European texts, which are themselves not as good as the English originals, having been edited for the European public. This is fabrication and backwards because it is well established that the German editions were the original and the pirate editions were taken from the German. But it makes his point that he is American. Specifically he calls out translator Pedro Rivas, El Popular (Lombardo Toledano's paper), and Editorial Cima in Mexico City. Previous Spanish editions of "Rebellion of the Hanged," "White Rose," and "Bridge in the Jungle" are pirated. He asks not to be judged by these inferior inaccurate texts. For instance in "Rosa Blanca," he says he never referred to Mexico in criticism, but an unnamed Republic in the south.

"Su primer nombre no es Bruno," he writes. The pirate editions all credited the work to the obviously German Bruno Traven. Traven explicitly disassociates himself from the "communazis." Who are the communazis? They are the German communist emigres that Traven believes are behind the pirate editions. The powerful labor leader Toledano was instrumental in gaining entry visas for German communists, has them in his employ, and possibly the financier for their publishing. (Zogbaum - "Vicente Lombardo Toledano and the German Communist Exile in Mexico"). Esperanza works for Editorial Masas, a communist aligned publisher started by the German exile Heinrich Gutmann, the same company - she may be the only employee - that published a translation of Marx by Pedro Rivas. She may even have helped the very editions Traven criticizes. She uses Editorial Masas letterhead to first inquire about film rights for Traven books, thus starting her association with him.

from the introduction (translated from Spanish) -

B. TRAVEN, is native of the western United States of North America, son of native Americans descended from Norwegian and Scottish respectively. He has just turned forty years, and he writes all his books in English. His first name is not Bruno, name awarded him by the comuninazis to whom the generous governments of Mexico and Argentina have given refuge. The author has no connection at all with those people, does not share his ideas neither his credos and regrets that some details, not foreseen in the laws that aid the rights of authors, as much in Mexico as in Argentina, have made possible the lamentable presentation of his work that has been carried out.

If these Spanish pirate editions were troubling Traven, if they were popularizing his name in Mexico, making it harder for him to remain the anonymous American, even calling him the German Bruno, it was a fortunate accident that Esperanza provided him with an unasked for translation.

However it was that Traven and Esperanza met, Traven not only grew close to Esperanza but also to her second cousin Gabriel Figueroa, the very successful Mexican cameraman. Gabriel and Esperanza were raised if not in the same household, in close proximity. They live in the same house at 1106 Coyoacan at least from 1941 to 1951. Traven stayed with them in Mexico City, either at that address, or the 39 Zamora address that Figueroa acquired. Traven becomes the godfather to Figueroa's son. Figueroa films several Traven movies.

The novel itself, Bridge in the Jungle, is a brilliant piece of writing. It has virtually no plot. An Indian boy slips from a bridge, is drowned, and buried. The bridge was built by an American oil company that cut costs by eliminating the railings. The narrator, Traven's stock American character Gales, is not involved except as bystander, and narrator for the mother's grief. The themes are death, a mother's love, acquiescence to fate. Traven writes it sometime in 1926-1927. Much of Traven's appeal is in the soliloquys between action. Either they ring true for you or they don't. An Indian mother's love of her child is as deeply held as any other mother. The Indian village is so small as to have no name. The people have as little as possible to have and not have nothing. Traven sometimes describes every movement of people who are the same as millions of others. Death and grief are universal, and he makes civilized people feel for a poor Indian boy and his grief stricken mother in an anonymous jungle. Chankin, "Anonymity and Death- the Fiction of B. Traven", says the story loses its punch after the recovery of the body, it occurs halfway thru the 200 page book, but it still makes its point, you are there in the village listening to the sounds of the jungle and seeing the faces. No one cares for these people except you and Traven. This is not the Great Gatsby.

from the Puente dedication

TO THE MOTHERS:

Of each nation,

Of each town,

Of each color,

Of each race,

Of each credo,

Of all the animals and birds,

Of all the creatures that live in the earth.